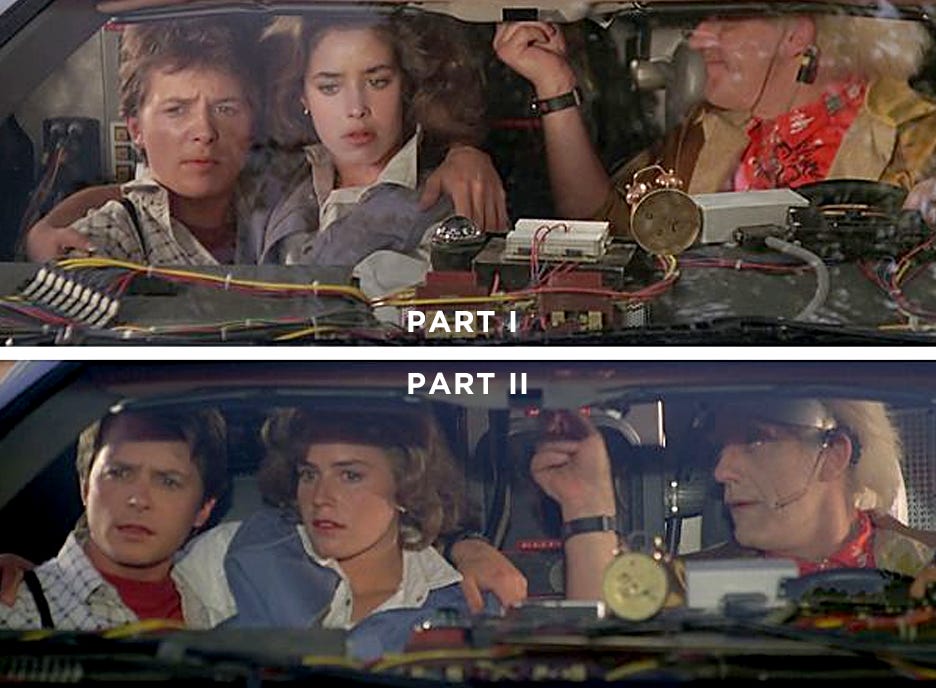

The beginning of Back To The Future, Part II is noteworthy for at least three reasons. First, because they recast Marty’s girlfriend Jennifer between movies (goodbye Claudia Wells, and hello Elizabeth Shue) which meant they had to reshoot the entire sequence shot for shot and beat for beat. Watching it with this in mind creates a weird imposter situation for me. It sounds like the original. It looks like the original… but it’s more mechanical. More rigid. The precision with which they copied the scene ironically made it feel different… (Just me?)

Second, it’s fairly well known that when Doc told Marty to bring Jennifer along at the end of Part One — writers Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale (“The Bobs”) had no plan for a sequel, and therefor no actual role for Jennifer in this future plot. This becomes hilariously obvious when Doc immediately knocks Jennifer unconscious and dumps her in an alleyway while he and Marty galavant into the rest of the movie.

Third: the tease. The end of Part One and the start of Part Two set up something positively thrilling — a flying DeLorean. Flying cars. Imagine the possibilities! My childhood brain went into overdrive… only for Doc and Marty to arrive in a future with — drumrolllll — traffic lanes in the sky. Yaaaay.

(Don’t get me wrong, I love the Future movies, warts and all. This isn’t a criticism of the Bobs’ creative decision. If flying cars were real, I’m sure the Department of Transportation would find a way to make driving them suck. )

ANYWAY — that third point is what I want to talk about. Because it’s a pretty good analogy for how a lot of writers feel when they first start out.

The onramp to screenwriting feels limitless. You’ve got ideas, passion, momentum. Your brain is buzzing. Your fingers are itching to fire out some killer dialogue. So you reach for guidance — and run headfirst into a sky full of traffic lanes.

“Always bold scene headers. Never use adverbs… Wait, don’t bold scene headers, bold character introductions. Show, never tell. There are three acts. No, five… Four acts — but you can also divide it into seven. Don’t bold anything…”

Formatting is scriptural, and Story a mere template. The art form becomes a science. And promising imaginations are dashed on the rocks of “no don’t do it like that.”

Well I have good news and bad news.

The good news is, there are no rules…

The bad news: … there are definitely rules.

I know. Stick with me.

There Are No Rules

If you’ve never read the screenplay for Rocky, by Sylvester Stallone — you should. The 1977 Academy Award Winner for Best Original Screenplay tells a great story, and its legacy speaks for itself.

Critically speaking, though, that script breaks all kinds of formatting conventions that would absolutely get flagged in a modern competition or festival. There’s telling instead of showing. Inconsistent pacing in action lines. Some character intros in CAPS, others not. And this is the polished draft.

Now imagine how it looked when Stallone — a novice writer — hammered out his first version (reportedly in three and a half days)

Here’s the thing: If your story works, your story works.

Formatting exists to aid the telling of that story — but it’s topical. It’s superficial — a perfectly formatted script and a poorly formatted script can tell the same compelling story.

This is not a call to disregard Industry standards (bad formatting certainly won’t do your career any favors). It’s an invitation to remember why you’re drawn to this craft in the first place — and to give yourself some slack. Even Oscar winners “do it wrong” on their way to getting it right.

I want to dive deeper into story mechanics eventually, but if you’re looking for powerful resources, books like The Anatomy of Story by John Truby, Story by Robert McKee, and Creating Character Arcs by K. M. Weiland are a great place to start.

There Are Definitely Rules

The Industry standard right-hand margin for writing transitions in a screenplay is 7.097 inches…

I’d love to meet the 1st AD who busts out a ruler and calls you on that .003 inches… Or would I hate it? I’d probably hate it. Legalism is the worst.

Screenwriting has two hemispheres: Story and Format.

In other words: the what, and the how.

You’ll hear a lot of rules about both, but format tends to be where a lot of focus is placed. For one thing, format is easier to appraise, and requires less critical thinking. Formatting is a technical discipline that depends on attention to detail — not emotional engagement. It’s also less subjective, so it can be critiqued with greater confidence. Your reader may not always know why a character arc isn’t landing, but they’ll know if your line spacing is off…

Why Formatting Exists, And Why It Matters

We’ll go into greater detail about both hemispheres in future posts, but for now it’s worth understanding why format matters at all. It’s not just arbitrary, and it’s not gatekeeping. It matters for a few deceptively simple but crucial reasons:

The Reader Experience - Screenplays are designed to be read fast. Producers, execs, assistants—they're all flipping pages at speed. Proper formatting ensures they get it at a glance:

Scene headings signal location/time instantly.

Action lines are tight and visual.

Dialogue is centered and easy to track

Timing and Pacing - Screenplay format serves as a rough timing mechanism — one page ≈ one minute of screen time.

If your pilot script is 70 pages, or your feature script is 130 pages, that’s a red flag before anyone even reads a word.

Proper format lets people feel the rhythm, spacing, and beats the way it might play onscreen.

Industry Standard = Professionalism - Formatting is like dress code for a job interview. It shows you understand the culture and requirements of the job.

If you ignore the rules, the assumption is: you’re not ready yet.

Clean formatting tells the reader: this won’t be a chore.

Functional Blueprint - The script, remember, isn’t the final product. It’s a blueprint for everyone in production.

Directors, actors, set designers, line producers—they all rely on clear formatting to budget, schedule, organize, memorize, and perform. Format is a shared language — and clear communication is key.

When the format is invisible, the reader is free to focus on your story.

When it’s off — even slightly — it distracts, and the story has to work that much harder to overcome the reader’s lack of confidence in the writer.

Rules Change — And That’s Okay

Writing for TV vs. film comes with different expectations — and that’s probably a topic for another post. But let me say this:

Even within TV, formatting is fluid.

My mentor — a brilliant and successful showrunner — insists on double spaces after a period. Not for grammar, but because it creates a cleaner visual rhythm on the page. She doesn’t bold her sluglines. Other showrunners do.

Neither is wrong. They’re just consistent. Over time, that consistency becomes the house style — a language the crew learns to read.

That’s also why script coordinators exist. In any writers room, you’ve got half a dozen professionals — all from different shows, trained under different habits. Writers’ drafts come with formatting quirks, inherited from old rooms or personal preferences. It’s the script coordinator’s job (hello!) to iron that out and make sure every episode reads like it came from one brain.

If you’re just starting out and worried about formatting — take heart. There’s support built-in to the process. There’s time to learn.

And nobody — nobody — expects you to get it perfect out of the gate.

Every Script Is A DeLorean

It looks weird. It runs on garbage. And when it works — it flies. But if you feel like you’re facing a sky full of limitations, just remember: the “rules” aren’t there to limit you. They’re there to help everyone else understand what you’re building.

Learn the rules. Use them well. Then build something no one's seen before.

We may not need roads… but it helps to know where they go.