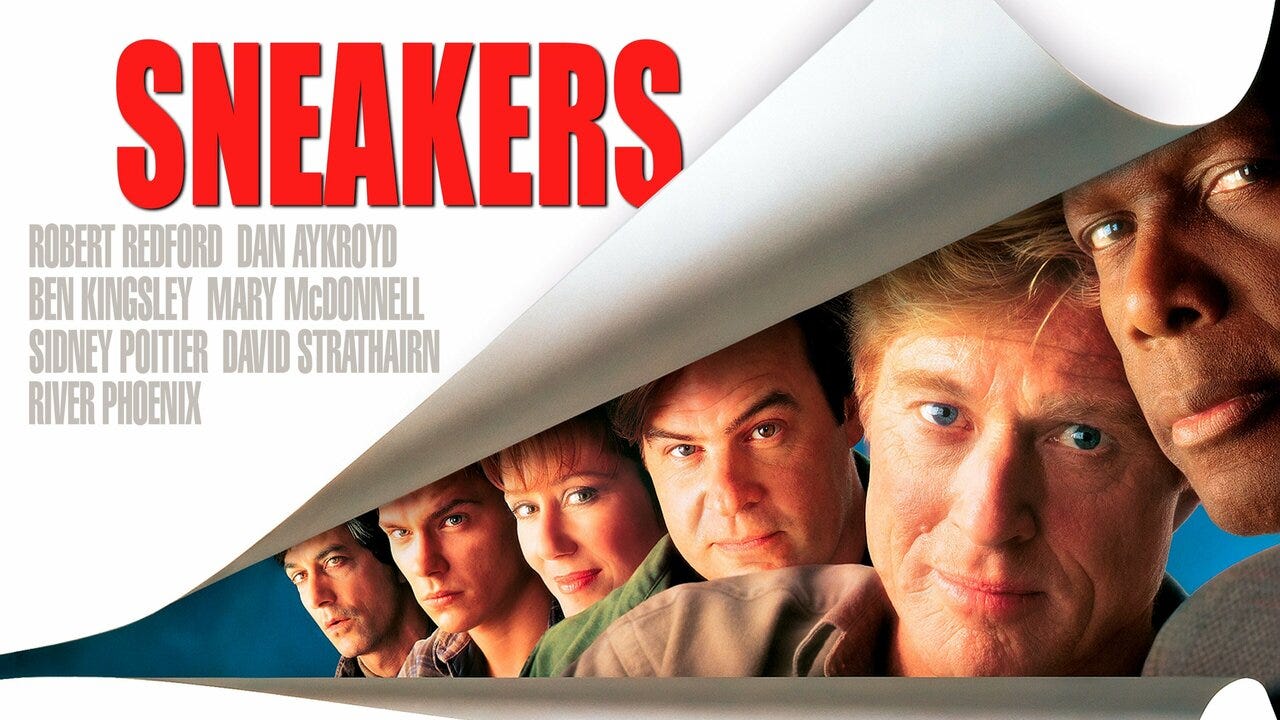

One of my favorite movies has a cool premise, a dynamic tone, and a thematically-provocative script. The composer crafted an incredible score, and every single member of the main cast has the word “Oscar” attached to their filmography — Robert Redford. Sidney Poitier. Mary McDonnell. Ben Kingsley. River Phoenix. David Strathairn. Dan Ackroyd. James Earl Jones.

It’s clever. It’s funny. It’s tense. It’s got heists, double-crosses, and River Phoenix huffing helium and throwing himself through ceiling tiles.

It’s about espionage — corporate, and otherwise — and the power of information, the corruption of those who control it, and the secrets we try to keep buried.

And for some unknowable, inexplicable reason, somebody thought a good title for this film would be…

This has always been a baffling decision to me. It’s not enough to ruin the movie, but the title has never felt right for this film in the way titles like “Star Wars” or “The Godfather” or “Ratatouille” fit theirs — and I’m convinced this is the principal reason Sneakers isn’t a bigger deal in the cinematic zeitgeist.

I have such a great affection for this movie — and I’m fascinated by this as a case study for the power a film’s title has on its marketability and its legacy. So I thought I’d dig into it a bit.

Sneakers (1992)

Robert Redford plays “Martin Bishop” — a man with a criminal past who goes by an alias and leads what we call in the real world, a “Red Team” — a team of specialists hired by companies to test their security protocols.

Bishop’s team successfully breaks into a bank and demonstrates for the management how easy it would be to walk out with stolen money. While waiting for their paycheck, a bank teller sums up their job nicely when she asks: “People hire you to break into their places, to make sure nobody can break into their places?”

“It’s a living,” Bishop replies, taking the check.

She smiles apologetically. “Not a very good one.”

After that (rather passive-aggressive) exchange, we learn a little more about Bishop and his team: the former-CIA man, Crease (Poitier), the blind computer genius, Whistler (Strathairn), the young wild card, Carl (Phoenix), and the electronics and surveillance specialist and conspiracy nut, Mother (Ackroyd).

This team’s dynamic is one of the film’s strengths. It’s natural, it’s comfortable, it’s filled with nods to past jobs and inside jokes. You believe this team has a history — and they’re fun to watch together.

That’s why — when they’re blackmailed into finding and stealing a powerful decryption chip (the “Black Box”) by some government types — not only are the stakes compounded, but we’re that much more excited to see how they come together to pull this off.

The plot thickens from there — and if you haven’t seen it, do yourself a favor and check it out. It’s very early ‘90s — it’s very “of its time.” But there’s a lot to love about this one if you’re into heists, buddy movies, or Ben Kingsley with a ponytail.

Why “Sneakers”?

The team occasionally refers to their jobs as “sneaks.” They do this twice (by my count), and it’s easy to miss in context. It’s not an industry term as far as I can tell, and it doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue.

Bishop asks, “Who’s got the report for the bank sneak?” — but if you ask me, “the bank job” or “the bank bust” or “that time we broke into that bank” all seem like more natural ways to describe their work, if not more natural to say.

Try it — say the words “Bank sneak” aloud, and tell me that feels like verbal lubricant. (Am I overthinking this?? … I’m probably overthinking this.)

Point is, the actual word “Sneakers” is never uttered in the film, nor does it have any narrative application… I’m not leaving out any context here.

First Impressions and Mental Branding

So: What’s in a title…?

The human brain is a pattern-finding maniac. When we encounter something new — a person, a song, a movie title — we immediately and subconsciously start categorizing it (What is it?), predicting it (What should I expect from it?) and preparing for it (What should I feel about it?).

While this is happening, we’re also applying “mental branding” to it. We’re processing it for clarity (I get it), emotional resonance (I feel it), and distinctiveness (It stands out).

A movie title holds inherent promise for the audience. It’s the first thing you know about a movie before you see a frame of it — it’s the first impression. And there’s nothing you can do to stop an audience from applying their own mental branding — so a lot of great titles lean into it.

Jurassic Park. Toy Story. The Godfather. Even Die Hard. These need no explanation on a gut level. You have a pretty decent shot at correctly guessing the genre, or topic, or vibes.

Now imagine if Die Hard was called Christmas Party, or Business Trip, or Ellis the White Knight…

Sneakers — you have to explain it. You have to qualify it. You have to keep saying, “No no, it’s not about shoes…”

It’s mental friction before we’ve even started.

But What About…

I know a lot of people who didn’t care for Barbarian (2022) — but I loved it. I knew little and less going into it — I’d never seen a trailer, I didn’t know who was in it — and I had so much fun watching it.

The title doesn’t really capture the movie’s subject matter. Aside from perhaps the overtones of uncivilized brutality, the word “Barbarian” doesn’t exactly scream “Airbnb-turned-nightmare-escape-from-surprisingly-sympathetic-killer-inbred-mother.” (Which, you might argue for this film, is sort of the point — the surprises are part of the fun.)

Either way— Barbarian is not a rare exception. There are probably as many obscure titles to great films as there are literal ones. The Shawshank Redemption — kind of meaningless, until you’ve actually seen the movie. Fight Club sounds like a low-brow actioner about dudes punching each other. I thought Parasite was some kind of elevated horror creature-feature until I saw it.

Style can override substance, and the movie can redefine the title — and you can’t underestimate the power of timing (culturally speaking).

BUT — and this is a substantially round and juicy “but” — these movies had to work that much harder because of their titles. They either had insane marketing pushes, big-time directors, or caught cultural lightning in a bottle.

Sneakers — despite its killer cast — had none of that.

Why “Sneakers” Doesn’t Pull It Off

Let’s do a quick experiment:

Google “Sneakers” and see if you’re surprised by what comes up.

If I called my film Puppies… it wouldn’t matter in the slightest that in my hypothetical fictional world, “puppies” is the term for some mystical alien fuel source that drives the local factions into eternal war. If you see “Puppies” on the poster, or hear your friends discussing “Puppies” — no matter how familiar you are with whatever insane IP this might have come from, your brain is gonna make one connection first:

“Sneakers” is not a common colloquialism for “guys who break into places.” It likely never will be, because the Shoe People got there first — and a long time ago. It would’ve taken a Marvel-sized marketing push and then some to redefine that term for this movie.

And for what? Does “Sneakers” really mean anything?

Scrabble Had the Answer

In my opinion, a far better title was staring the filmmakers in the face.

There’s a sequence around the midpoint of the film, where the team is celebrating a win with a little party. Bishop, his sort-of girlfriend Liz (Mary McDonnell — who is awesome), along with Crease and Mrs. Crease, play a friendly game of Scrabble (killer party, guys.)

Bishop’s letting his mind wander when he realizes that the job’s code name they were given, “SETEC ASTRONOMY” doesn’t really mean anything. It’s an anagram, designed to conceal the true nature of the project. Bishop upends the Scrabble board, and gets to work finding the tiles to spell it out, then rearrange.

Meanwhile, across the workshop, Whistler, Carl, and Mother start playing around with the newly-secured Black Box — the code-breaking machine. Bored curiosity quickly grows to nervous awe when they realize what they’re dealing with — instant access to highly-secure websites and systems, like power grids, air-traffic control, and the federal reserve.

This sequence quietly and expertly ratchets up the tension — helped immensely by James Horner’s perfect accompanying score — as all our main characters slowly realize they’ve just painted huge targets on their backs.

“There isn’t a government in the world that wouldn’t kill us all for that thing.”

And as the penny drops, Bishop finds the right Scrabble combination — the real name of the project:

Simple. Clear. Thematically on-point. It has a strange, quiet menace to it that makes it feel enticing and dangerous — and it implies the inevitability that something will be done about this.

But that’s just my pitch.

What do you think? Have you seen (or even heard of) Sneakers? I'd love to hear what you would've called it — or whether you think “Sneakers” actually nailed it.

Favorite underseen movies welcome too. Let’s make some noise for the good stuff that slipped through the cracks!

Thanks for reading.

Not to mention the tone-deaf trailer. They tried to market it like a goofball comedy. As if someone heard "Ackroyd" and just assumed, then never course-corrected as the footage came in. "No, but Ackroyd!"

If you *wanted* to tank a movie, this is, step-by-step, the prototype for how to do it.

...

And now I have the score from this scene stuck in my head, and my job suddenly feels so much more urgent.